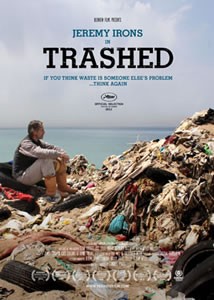

Trashed challenges world to change habits

The director of a new documentary on waste, Candida Brady, exclusively talks to Philip Chadwick on global challenges, the film’s stunning locations and how it intended to avoid pointing the finger of blame at packaging.

The director of a new documentary on waste, Candida Brady, exclusively talks to Philip Chadwick on global challenges, the film’s stunning locations and how it intended to avoid pointing the finger of blame at packaging.

Trashed is a documentary narrated and presented by the actor Jeremy Irons, who visits locations around the world where waste is poorly managed causing health issues and polluting the nearby environment. The film looks at landfill, incineration and waste dumped into the sea. Trashed doesn’t always make for easy viewing, especially for anyone in the energy-for-waste sector and plastics industry. Packaging comes under the spotlight as well and, while Irons appears none too impressed with “packaging professionals”, the film does make the point that the majority of materials can be recycled. The model that’s held as a fine example of waste management is in San Francisco – a city which has a zero waste policy, which appears to be embraced by the inhabitants. Director Candida Brady, who spent two years to research and film Trashed, took the time to discuss the movie with Packaging News.

What attracted you to making a documentary about waste?

My interest in waste has been growing over the years and when you have children it ramps up a level when you see all the things they have. I started to wonder what was happening to all this stuff perhaps because I’d grown up with less. I had been looking at water as a documentary idea but I was then approached to do a film on incineration. Over time I realised that waste was the huge problem for the world.

How did you get Jeremy Irons involved?

He had done some other projects for us in the past and we had been neighbours for some time. I knew that he never wasted anything. He tends to use things until they wear out. I thought it was something that would appeal to him and it did.

There are some incredible locations in the film. For example, a waste mountain in Lebanon, a river full of rubbish in Indonesia and an incinerator next to a farm in Iceland. How did you source some of the locations?

My research went on for some time. I wanted to pick some horrendous examples but visually the impact had to be pretty big. Film is a big canvas and you have to ramp up the size of everything. The size of the [waste] mountain in Lebanon made that point very well. But there was another place in Hungary I was told about where they had built a landfill in the middle of a housing estate. There was also somewhere in Hong Kong where they pushed all their rubbish into the sea. In Iceland, there was this beautiful, untouched and very clean place and there was this horrible story. It wasn’t isolated – all three of Iceland’s incinerators had been breaching at that point. I chose the story to show the beautiful location that had been poisoned.

Did you get the chance to speak to the companies operating the incinerators?

I put requests to various people but let’s just say that we drew a blank. It was met with a polite reluctance.

At one point during the film, Irons appears to deride packaging. Was this fair?

At one point during the film, Irons appears to deride packaging. Was this fair?

Jeremy Irons made a point about over packaging rather than packaging. Half way through filming and research, I felt that this is such an enormous problem, there shouldn’t be any finger pointing. With films of this nature you can’t say ‘this is the bad guy’. I did not want to pick on packaging as it’s not the industry’s fault. If anything, we all need to wise up and work together to get better solutions.

There was a shop featured that encouraged people to bring in their own packaging and refill products. Is that a model we should explore?

I think it’s a very effective solution. It’s automatic to just take a plastic bag [provided by] a shop. Many people ask for a bag even for the tiniest thing. It’s just a habit that we’ve got into and we need to be made aware of it to be changed.

The film also looks at food waste. Does packaging have a role to play in the protection of food?

For transporting, packaging is absolutely essential and hard plastic has a place in society. If it’s non-toxic and can be recycled it’s an essential part of keeping something fresh. However, I have been shocked to see staff in supermarkets chuck all the unsold food in the bin. Much of it would have been fine to eat that evening, perhaps a few days afterwards.

Is San Francisco a good model and why do you think it works?

San Francisco has been doing zero waste for a long time. They have wonderful, clear signposting. As a visitor you are led to do the right thing the whole time. If you look at the back of our packaging, I think our signposting could be much simpler.

How can things change?

The film is a first step. There are lots of wonderful organisations everywhere and terrific people doing incredible things. It’s going to take all levels of business working with government. But the will of the people is there – I’ve seen it. Once people know the scale of the problem then they would feel responsible. Imagine if we all stopped taking plastic bags – that would make a huge difference to the world. Once you start noticing plastic bags in the wild you become obsessed with them especially when you see them stuck in every tree and bush. We are all responsible for our own waste.