400 PPM and the Next Four Years

What current atmospheric carbon dioxide concentration tells us about the need to stabilise the global climate and the need for a step change in government, city and business action.

Introduction

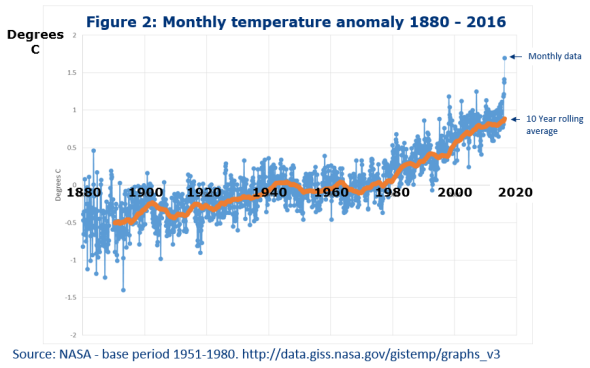

If as expected atmospheric CO2 averages 400 parts per million (ppm) this year, for the first time in over 800,000 years, 2016 may well be regarded as a pivotal year. In the three decades since the first presentation of man-made climate change to the US Senate, the presenter of which subsequently proposed 350ppm as the ‘safe’ limit, greenhouse gas concentration has accelerated rather than declined. Monthly peak anomalies in global warming have edged close to the UN IPCC ‘best efforts’ threshold of +1.5°C above the pre-industrial average, and sustained regional temperature anomalies have extended beyond +5 °C. Northern hemisphere ice masses have declined; sea levels have risen; extreme weather events have increased in frequency.

With less than four years to go to 2020 it is timely to take stock and reappraise what needs to be done to stabilise the global climate. Reaching 400ppm crystallises a stark choice between two scenarios:

• Continued acceleration of greenhouse emissions and climate change culminating in substantial forced changes in global climate, land use, factors of production and patterns of demand, and corresponding investment in adaptation measures (in UNFCCC terms, a ‘Paris fails’ scenario).

• Managed reduction in emissions through major and rapid changes in technology in energy, transport, production and consumption through nationally determined policy initiatives attempting to hit a sweet spot between national economic competitive advantage and environmental responsibility (in UNFCCC terms, a ‘Paris succeeds’ scenario).

Three key players determine which scenario prevails: Governments, Municipal Authorities/Cities and Corporates. They have influence over the majority of emissions, determine resource allocation, and exert a profound influence over both financial prioritisation and consumer choice. Their actions in the next four years will determine whether emissions and climate change begin to slow, or whether they continue or even accelerate.

Recent climate change and implications

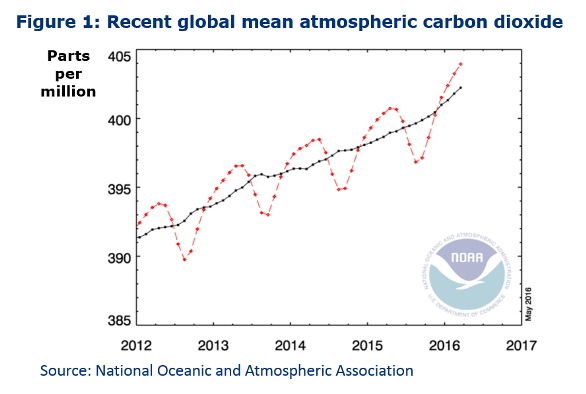

Having tipped 400ppm in March 2015 (Figure 1), 2016 will probably be the year when the global mean atmospheric CO2 concentration is at or above this level; the consequence of high industrial, agricultural, transport and domestic emissions, together with emissions from natural sources induced by anthropogenic change such as retreating permafrost, and potentially a reduction in the carbon-sink effect of natural systems[i].

In parallel, the atmosphere has warmed (Figure 2) and northern hemisphere ice masses have depleted to their lowest recorded extent.[i] Sea levels have risen to the highest levels mankind has ever recorded. Unprecedented extreme weather events have impacted many parts of the globe, from record summer and winter temperatures in Australasia and Europe to flash floods and winter droughts in America.

Three key players

Governments, Municipal Authorities/Cities, and Corporates are the key players. They control the levers necessary to effect a successful low-carbon transition. For Governments and Municipal Authorities, social and economic opportunity will be balanced against political risk. For Corporates, the risk to assets and economic return will need to be mitigated while both the potential return and the potential risk will need to be managed across technologies, markets and operating models, potentially opening significant commercial opportunities. For each, there are some fundamental and enormously important issues they should be addressing now if the world is going to combat climate change.

(1) Governments

The key consideration for Governments (and Governmental bodies) is whether the rate of policy change that is required can be delivered given political and other constraints.

In a scenario of continued acceleration, the effects of climate change present a significant threat to established government approaches. To the extent that adaptation will be possible, large-scale investment in adaptation strategies will become a necessity, particularly relating to sea defences and protection against extreme weather events, but the scale required will be affordable only for wealthier nations. Even in wealthier nations, financing models will need to change to monetise adaptation benefits. To maintain global security the wealthier nations will almost certainly have to increase overseas aid budgets to support a minimum level of climate relief.

To deliver a scenario of managed reduction policy makers will need to develop policies that deliver a step change in low-carbon investment, linking economic return to environmental capital in ways never before attempted yet enabling societies to evolve and prosper. Managed reduction will require significantly increased deployment of low carbon technologies, both to reduce demand through improved energy efficiency, and produce cleaner energy, including through renewables, as well as enhanced innovation so critical technologies such as energy storage and CCS can be developed and deployed cost effectively.

The Paris Agreement made an important commitment to support action to adapt to climate impacts and develop low carbon energy systems in developing countries. The OECD estimates that US$62 billion has already been pledged by developed countries so far towards the goal governments agreed in Copenhagen in 2009 to invest US$100 billion per year by 2020. The Agreement confirmed that there will be a new goal to provide more than US$100 billion per year from 2025. Of course, the scale of overall investment needed in low carbon technology to make the sort of transition required by the long-term goals dwarfs this amount. And the text remains silent on how or through which mechanisms these funds will come. However used wisely, this level of funding will play an instrumental role in creating clean technology markets globally, leveraging far greater private sector investment, and enabling innovation to take place which reduces the cost of low carbon technology.

The Paris Agreement also defined a process to review progress versus countries plans and increase action to meet a “managed reduction” strategy. This is very important as countries both need to articulate a clear set of detailed underlying policies and actions that will deliver their INDCs, and to define the economy wide deep emission reduction pathways out to 2050 and beyond that will minimise the cost of the transition and maximise their national competitiveness in the context of this global challenge.

Physical supply chains are likely to suffer from scarcity and even in some cases breakdown (e.g. crop failures), risk factors and insurance premiums will rise (e.g. for extreme weather events), supply costs may rise or simply become more volatile, and energy scarcity and cost may become a key business factor. Whether or not there is strong legislation mandating action, many businesses will look to move independently and adopt leadership positions so that they are more efficient, able to profit from related cost and revenue opportunities, and are able to trade on improved reputations.

Managed reduction presents huge challenges for corporates invested in conventional carbon-intensive infrastructure, and affords genuine opportunities for innovative organisations.

Currently, leading corporates have set out longer term targets and focused on energy efficiency. A few pioneers have established innovation investment and supply chain re-engineering strategies aligned to corporate environmental targets. Many others are picking off the low hanging fruit (such as LED lighting), but many firms are doing nothing – effectively waiting to be regulated. Among leading firms good corporate governance has become associated with good environmental management, and many of the strongest companies – Marks & Spencer, Unilever, Walmart, Toyota – are at the leading edge. All of these have, at some level, understood and acted upon the long term risks and opportunities to their business around climate change and sustainability.

Managed reduction calls for greater alignment between a sustainable climate and corporate strategies, and for the extension of corporate sustainability strategy from direct operations to supply chains, and from production and delivery to in-use, end-of-use and recycling.

Science-based targets that align strategic delivery with desired climate outcomes will need to be set (and delivered) in both direct operations and through supply chains. Supply chain engagement will lead to more circular supply chains. Measurement of emissions will need to embrace both in-use and full lifecycle impacts. Transformational innovation will progress to zero-carbon and carbon-positive goods and services leveraging bio-resources and carbon-sinks. Rigorous operational efficiency will need to drive reduction in energy use, resource use, working capital and embedded emissions. The cost of capital for high-carbon operations is likely to increase, together with carbon and energy taxes, driving stronger focus on carbon efficiency and placing the spotlight on potentially redundant business models, high risk portfolios and potentially stranded assets.

Hence finance companies and asset managers will take steps to ensure that environmental costs and benefits are factored into investment decisions, and level playing fields are established for the cost of capital, production and consumption. They will need to embrace consistent global carbon pricing and trading, mandatory and independently-verified carbon reporting, consistent international trade regulations that provide for consistent energy and carbon efficiency, and visibility of true lifecycle carbon impacts.

Together corporates and finance companies exert strong influence over consumer choice and demand. The true environmental impacts and costs of consumer choice – in diet, product purchase, energy use and general consumption – need to be made visible, comprehensible and above all actionable.

Overall managed reduction is expected to help create greater opportunities than risks for business. It will help create larger markets for low carbon technologies and services, which will be a major source of future revenue and jobs. The size of the prize was underlined starkly in Paris by John Kerry, the US Secretary of State, who said this shift towards a low carbon economy was among the “greatest economic opportunities the world has ever seen.”

Conclusions

400ppm is a data point and a point in time, but crossing it potentially marks a pivotal year. It is uncertain whether the world will continue acceleration of greenhouse emissions and climate change or deliver a managed reduction in emissions through unprecedented changes in energy, transport, production and consumption. What is clear is a growing consensus that a managed reduction presents a more attractive future than the high risk world of continued acceleration.

Governments, Municipal Authorities/Cities, and Corporates face a medium-term planning horizon characterised by unprecedented potential complexity. To navigate that complexity it will be necessary to bring these perspectives together to allow sharing of expertise and enable clarity of policy and strategic direction.

Making the right choices, developing strategies that are both resilient and adaptive to various outcomes, and backing the right actions and technologies in the next four years will determine not just whether these organisations are successful over the next twenty years, but indeed whether they continue to exist.

[i] E.g. Galen A. McKinley, Amanda R. Fay, Taro Takahashi, Nicolas Metzl (2011), Convergence of atmospheric and North Atlantic carbon dioxide trends on multidecadal timescales. Nature Geoscience, July 10, 2011

[ii] National Sea Ice Data Center

[iv] IPCC Climate Change (2014), Synthesis Report Summary for Policymakers

[v] Economist Intelligence Unit: The cost of inaction: Recognising the value at risk from climate change, April 2016